Trigger warnings – Violence, Physical Abuse, Death

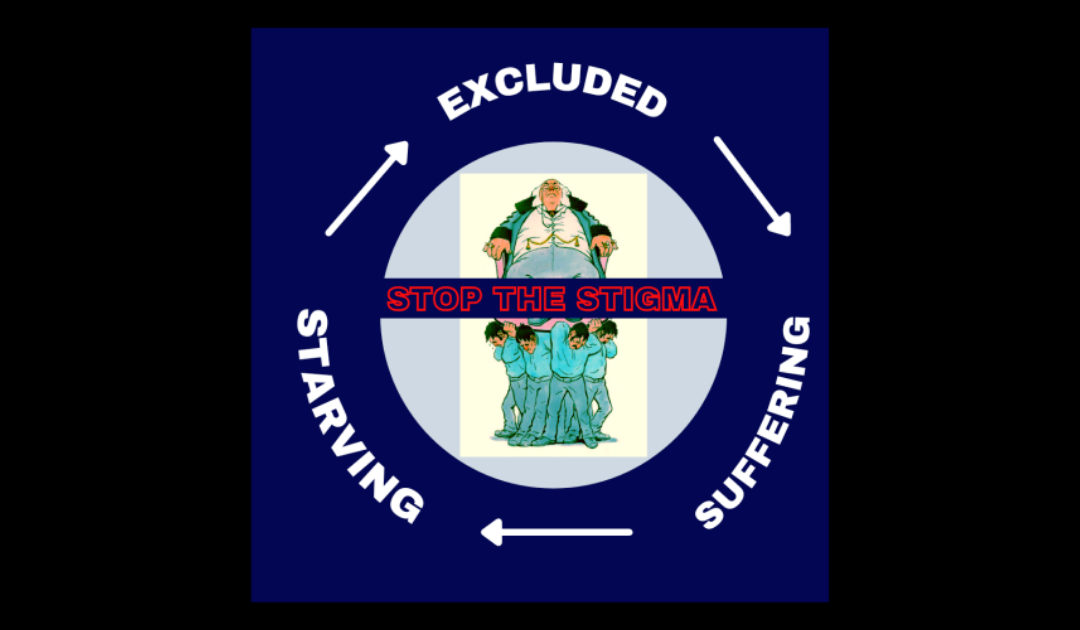

Undoubtedly, the hierarchical aspect of our society has a huge impact on our lives. Based on wealth, educational attainment, occupation, income, sociologists generally posit three classes: working (or lower), middle, and upper class. The dynamics of the groupings of individuals into different classes is constantly affected by various factors, especially the pandemic. Social exclusion, misuse of power, labelling and stereotyping is adversely affecting the lower class at an increasing level. Not all stigmatisation is overt, sometimes, the majority of stigmatisation against a community is subtle. This kind of discrimination affects people’s opportunities, their well-being, and their sense of agency and identity. It is a silent killer and individuals begin to internalize the prejudice or stigma that is directed against them, manifesting in shame, low self-esteem, fear and stress, as well as poor health. This is prominently seen among the people belonging to the lower classes.

As stated a million times before, the virus did not create inequality among us individuals but exposed the already prevalent divisions. Let us go back to the beginning of the pandemic. Lockdowns across the world were the first steps towards othering. An inbuilt bias towards the privileged when it was presumed that people could stay locked up in their homes and survive, without considering the fact that how would workers, daily wagers, labourers, house helps, street vendors, barbers, plumbers, mechanics and many more survive even for a day without work with their hand-to-mouth existence.

We all remember the time our country went into a nationwide lockdown on 24 March 2020. The following months were extremely hard and traumatising for the labourers who were trapped in different states, with nowhere to go. A 12-year-old girl died after walking 150km from the southern state of Telangana to Chhattisgarh state in central India. She wanted to get home and feel safe during those uncertain times. She had walked for three days when she died, 14km from home. This was the story of several workers. The workers who returned to the city of Bareilly, in the Northern state of Uttar Pradesh, were doused in a chemical solution in order to ‘disinfect’ them. Twitter users outrageously called out the barbaric treatment meted out to our workers. Instead of helping them reach their homes safely, for the following months after the lockdown, our workers were ill-treated at a makeshift, packed shelter houses by the officials in charge. They were hungry and cash-strapped for months and it brought colossal shame to the entire country as the officials excluded the workers from protection, food, and any form of medical assistance. Fear of the Coronavirus spreading was used as a justification for this inhuman treatment. The stigma of being poor was highlighted as the government made arrangements for bringing back Indian students, tourists, and others who were stranded in foreign countries, but paid little attention to the plight of these workers who were stranded only a few states away from their homes. A recent report prepared by the Centre for the Study of Developing Societies (CSDS) in collaboration with Common Cause India, a Delhi based non-profit titled Status of Policing in India Report 2020-21: Policing in the Covid-19 Pandemic, showed that those belonging to the lower class of the society, based on income level, were more scared of the police, including that of physical violence during the lockdown as compared to other classes. 49% of police personnel reported frequent use of force against migrant labourers and 33% used force to prevent those trying to enter shelters. Socioeconomic inequalities have left families across the world yearning for basic human rights, education, housing and health protection.

Jalinah Jamaludin, a homemaker, often fears that the COVID-19 virus could infect her whole family due to their living conditions. She lives with 11 other family members in a two-room rental flat in Tampines, Singapore. This cramped living situation is the story of low-income households and those who work in manual jobs with typically low salaries, across the world. They have no way to adhere to isolation if one of their family members fall sick nor can they afford to miss a day of work and follow social distancing norms due to their working

conditions. A report published by UNESCO, UNICEF and World Bank on 28th October 2020, expressed that school children in low and lower-middle-income countries have already lost nearly four months of schooling since the start of the pandemic, compared to six weeks of loss in high-income countries. The digital divide since the beginning of the pandemic has only worsened over the past year. Access to online education among the rural institutions for each and every child has become a pipe dream, with glaring obstacles to the affordability of laptops, phones and wifi connections. Children belonging to lower class families have also sacrificed their education to work in order to earn money. For some lower-class individuals dying from starvation is much more likely than dying from the virus. It is a simple task to attribute these atrocities to the pandemic. If we cannot contribute to helping, we should at least have the humility to acknowledge that the pandemic has only exacerbated pre-existing, well-rooted maltreatment.

Discrimination against the lower classes has been fueled by the pandemic culture.

Dr Jagdish Hiremath, a leading cardiologist at India’s ACE Healthcare, noted in a tweet – “Social distancing is a privilege. It means you live in a house large enough to practise it. Hand washing is a privilege too. It means you have access to running water. Lockdowns are a privilege. It means you can afford to be at home. Most of the ways to ward off (the coronavirus) are accessible only to the affluent.”

The pandemic culture in itself is the biggest discrimination between the different classes.

As stated previously, this silent form of stigmatisation has unfortunately crippled the individuals from lower classes to progress through their living and working conditions during the pandemic. The World Bank estimates that the pandemic will push 150 million people into extreme poverty by the end of 2021, where the new poor will be in countries already having high poverty rates. This states an unfortunate crisis at hand, where we have clearly failed to help our fellow humans in a time where they face stigmatisation along with a life-threatening virus.

– Urveez Kakalia and Ferangiz Hozdar.